I often hear people taking about the need for self steering teams. The logic is that organisations are getting ‘flatter’ and the reduction in hierarchy and managment layers needs to be compensated by making teams self steering. I agree that organisations are better of flat, and I agree that this requires a different kind of management and teams. However, I don’t think self steering is the right terminology.

For one, any terminology is flawed simply because giving something a name distracts from the fact that we should probably be talking about what we do, not about what we call it. But if I would have to choose, I follow my friend @arieenpaul who argues we need self organising teams rather than self steering teams. The way I see it is as follows:

For an organisation to function well, we need direction, effective decision-making, a degree of control, effective methods to get stuff done, and motivated professionals to take care of this.

- First, you need to determine ‘why we do things’ (or if you insist on terminology, a purpose, raison d’être, dot on the horizon, etc). Whatever shape or form you give it, it should simply describe how your organisation defines value. Not success, but value. It doesn’t have to look glossy in a folder or an annual report. It doesn’t even have to be one definition. As long as it describes the benefits to the organisation, it’s employees and other stakeholders if it manages to achieve planned results.

- Secondly, you need to have some kind of control over ‘what it does’. An organisation needs to be clear about what it chooses to do and what not. Of course, any decision should be guided by the ‘definition of value’. This sounds obvious, but often (or almost always) organisations suffice by defining when something is done, when they are successful. Though there is value in knowing you achieved results, it might be wise to also evaluate the results themselves.

- Finally, you will want to determine ‘how to do things’, or what needs to be done to achieve results, what time it will take and who needs to be involved.

Now, the main question is: If you are a manager, do you need to decide how things get done? Isn’t that something you could leave to the professionals in your team? Another question is: If you are a professional, should you determine for yourself why you do the things you do, what is valuable and what not? Isn’t that something that should be aligned across the organisation?

I think that you could separate two important roles in a company (like we do now, the manager and the team member). The ‘manager’ should help determine the value of different options a team has and reconcile with other teams across the organisation if they have the same idea of what’s valuable. The ‘team’ should determine what it would take to get the options realised should they be chosen. Once this is done, they together are best positioned to make the cost-benefit analysis needed to make a decision. So in short, the manager provides the ‘benefits view’ and the team provides the ‘cost view’. The manager connects the team to a higher purpose and the team connects the manager to practice.

This means that the manager should still do the steering and -therefore- the teams should not be self-steering. And vice-versa, the manager should not be involved in organising the work (certainly nog micromanage), but leave this to the ‘self-organising’ team. The manager can lead, the team can be autonomous.

Are you a talent, or do you have a talent? Are you a failure, or do you fail sometimes? In the video below, Derek Sivers (indeed, the one from the dancing guy video) describes why he thinks we need to fail and be proud of it. Along some experiments he argues that failing leads to:

- More effective learning. If we always do what we did before, we will get what we have, and not learn a lot. It is fun to realise we are good at something by doing it over and over again, but it brings us little in terms of growth. Like physical training, getting better has to hurt a little.

- Growth mindset instead of a fixed mindset. If you believe you can grow your own talents, rather than that talent is innate (you either have it or you don’t), you will expect that putting more effort in learning will lead to better results. And it does. This is a nice link to the concept of ‘expectancy’ (See post “Three types of expecations that drive motivation“).

- Experimentation. By seeing everyting as an experiment, allowing things to go wrong, we learn more. It helps to stretch our experienct to areas that we would never have experienced if we would aim to succeed in everything we do.

For the full explanation by Derek Sivers, see the following video:

For the full explanation by Derek Sivers, see the following video:

I guess we all agree feedback is crucial for our self-awareness, especially for our awareness of our impact on others. As it’s difficult both to receive and to give feedback it remains a challenge for almost everybody. Having some insight into why we either do or don’t hear feedback, how we receive it, and how we respond to it can make us better at receiving feedback. It can also help to not make the feedback bigger or smaller than it was intended and prevent us from developing a distorted sense of self.

Sheila Heen describes three factors contributing to how we respond to feedback:

- The baseline or setpoint. Our base-happiness in the absence of other events in our life that influence our happiness. Some people are by default on a high level of happiness, say an 8, others can have a more negative baseline. A negative baseline might result in a reduced ability to hear positive feedback.

- Swing describes how far off our baseline we evaluate the feedback. If feedback is very negative, and we have a very positive baseline, then the swing will be very big. A big swing usually means a big impact on our sense of self.

- Restore time is the time it takes for us to go back from our level of happiness under the influence of feedback to our baseline. Sensitive people might take longer to restore than unsensitive people.

Next to influencing our restore time, our sensitivity has an effect on the perceived impact of the feedback we give to others. Insensitive people might give more extreme feedback (larger swing) because they don’t think it is a big deal

See Sheila Heen’s short video on the psychology of happiness and feedback:

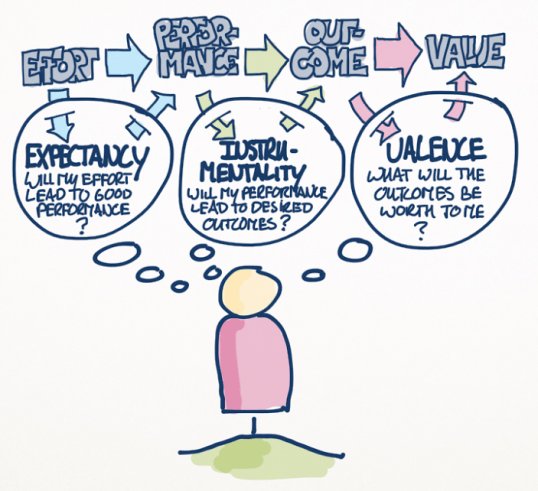

How do my expectations about a task influence how motivated I am to perform the task well? According to Vroom, there are three types of expectations that influence motivation: 1) Expectancy, 2) Instrumentality, and 3) Valence. These three influence if and how much effort we put into a task and our perceived probability of success. It affects all the choices we make.

Expectancy is the perceived probability that effort will lead to a good performance. Logically, this perception is influenced by our belief in our abilities to perform tasks in general (self-efficacy), the difficulty of the task and our perception of the amount of control we can exercise on reaching the outcome.

Instrumentality describes our perception on how likely it is that our performance leads to desired outcomes, like recognition from others, a reward, or a sense of accomplishment. There is an element of trust related to this expectation, as some outcomes might come from within ourselves, but others are provided by other people in our environment. Do we trust good performance will be rewarded?

Finally, valence is what we expect will be the value of the outcomes to us. If positive, logically, we are likely to put in the effort and perform the task, if negative we will avoid it, and if neutral we are indifferent.

The three together can be seen as a formula, strengthening or weakening each other to determine the strength of our motivation: Motivational force = expectancy x instrumentality x valence

Think about it… what is motivating you to perform well at work or in sports? Do you want to be better than the rest? Or do you want to be the best you can be? In other words: do you want to win from others, or from yourself?

Having a relative versus an absolute measurement of success and failure probably has a big effect on the choices we make, and the way we work together with others. For instance, if I measure myself relative to others, success can be achieved by becoming better myself, but also by making others look bad. And winning or loosing a match might be less important if I focus on succeeding in doing all I set out to do.

In the following talk, coach John Wooden explains his view on the difference between winning and succeeding. In his opinion, succeeding is more important than winning. He supports this by a couple of lessons that can be summarised (with some interpretation) as follows:

In the following talk, coach John Wooden explains his view on the difference between winning and succeeding. In his opinion, succeeding is more important than winning. He supports this by a couple of lessons that can be summarised (with some interpretation) as follows:

- The end (result) is less important than the journey (effort)

- Focus on succeeding leads to a focus on what you control yourself and on what you can learn from others

- Focus on character (succeeding), rather than reputation (winning), or:

- Focus on who you really are, rather than on what you’re perceived to be

- The score (in a match) is not an objective, it’s a byproduct

- Trust your own judgement over others’

Vulnerability, curiosity, doubting and asking questions are often mentioned as important traits for people in leadership positions, or for professionals in general. I find it interesting to see how we can stimulate these traits by getting better at asking questions. To explore ‘the art of asking questions’ I’ve conducted a little experiment, ‘crosstabulating’ the three most basic questions with each other, thereby generating nine different types of questions.

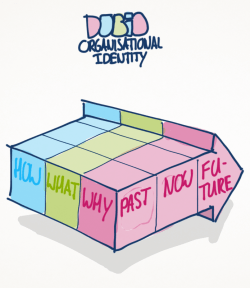

We all know the basic questions “how?”, “what?” and “why?”, obviously. Some questions are easy to classify as ‘a why-question’ for example, while others are more difficult to categorise. In the drawing below, I explore nine different types of question consisting of a ‘primary doubt’, based on one of three basic questions, supplemented with a ‘secondary doubt’ to make the question a little bit more comples, and thereby -hopefully- more valuable and insightful.

As you can see, the ‘complex’ questions can be described as ‘what-why’ or ‘how-how’ questions for example, and form quite distinct categories. I can imagine that individuals might have an ‘unconscious’ preference or bias towards certain specific categories, therby neglecting other types of questions. If this is indeed the case, broadening their ‘question repertoire’ might be helpful.

Q: Do the categories work for you? And do you think ‘expanding your question repertoire’ is interesting to do?

Why are we here? Where are we going, and how will we get there? How can we get all the noses in the same direction? What questions do we ask ourselves during the process of creating a strategy, and what questions do we answer while communicating about it? Being fully aware of what we are doing, how we do it, and why is crucial both for our own understanding of ‘our meaning of life’ and for engaging others to buy into our ideas.

This document describes what I think are some elements of good strategic communication, whether on a department level or on the level of a project. See document: The art of strategic doubting

Would be very curious to hear your thoughts on it!!

For learning & development professionals in organisations, I see two major challenges: 1) To distill out of ‘the business’ what learning and development needs there are, and 2) when we are done in our ‘l&d lab’ to ‘sell’ learning solutions back to the business and ensure transfer of learning. So, if it’s so hard to take it out, and equally hard to put it back in…. why take it out at all?

In my opinion the language we use to intermediate between the demand (the learner) for and the supply (the l&d professional) of learning solutions is very much focused on what we learn. What do we need to learn? What topics are relevant to my role? What have I learned in this course? What will be in the exam? You could argue if that is the most appropriate language since learners talk amongst themselves about why they want to learn (Excel in my job, increase job security, master a skill, satisfy curiousity) and learning & development professionals talk about how we can learn most effectively (quality training, learning methods, learning on the job). Agreed, it works to match supply to demand, but there is a risk the match is too superficial and responsibility (or rather accountability) for the learning solution is deferred to the learning professional while it belongs to the learner.

We often talk about stimulating learning on the job in combination with formal training and about the transfer of learning from a training, but simply viewing (professional) learning as something seperate/different than working (even when done in the same place) is unnecessary in my view. Why call a meeting with a trainer a training, and not a meeting? Why call a trainer a trainer and a learner a participant if we want the responsibility of the learning to be with the learner? Learning should be part of working. It is ‘meta-working’ (evaluating and improving our work). This is not the same as ‘learning on the job’, and I’d rather call it ‘performing consciously’. See also my post “Is learning the same as performing consciously?”

The solution in my opinion does not lie primarily in finding new learning methods or strategies, we are pretty good at that, but more in how we ‘label’ learning initiatives and the people and departments involved in learning. It’s more a language thing than anything else. We should aim to keep learning where it’s most valuable and least distracting: in the work. This does not mean it should always take place in the same physical location as the work itself by the way. And I can imagine there are many exceptions to this, but I think it’s more true than we currently believe and put into practice.

Why do we use learning objectives to describe what the aim of a training is? They are difficult to write, difficult to remember during the actual learning and often not really representative of the training in hindsight. This is even more the case in learning on the job. Is the solution to this to become better at writing learning objectives and reminding learners of them during the learning process? Or could there be another solution?

I like to think that if we would use ‘learning questions’ instead of ‘learning objectives’, in many cases we could be better off. To investigate, I’ve made a comparison.

|

|

Examples:

|

Examples:

|

| Learning objectives aim to focus our learning towards the desired learning outocomes. This focus helps to seperate important elements in the offered content from the unimportant ones based on their fit with the desired outcomes, but they also make us overlook other, potentially interesting elements. | Learning questions aim to make us curious about a certain topic with the intent to make us search for valuable outcomes, but not necessarily the ones we expected. In this way, it might stimulate serendipity (the talent to find things we didn’t look for but do need/want) |

| Objectives can be experienced as being pacifying rather than activating in a way that they limit our autonomy in choosing what elements contribute to reaching a desired outcome. E.g. Example 3 seems to limit us to learning presentation skills |

Questions might be more activating to the learner as they can stimulate learners to think about possible answers, or possible ways to reach the desired learning outcome. In example 3, the learner might set out to discuss his/her work to his/her mother in law or -even better- start blogging about it 😉 |

| Learning objectives, in my opinion, stimulate a ‘climate’ where knowing the answers is seen as a sign of success. Knowing the answers can obviously not be a bad thing, unless it makes us disregard (people with) good questions and challenging ideas. In example 2 we are told negotiations have phases and there are identified tactics and behaviors we should apply to be successful in negotiations. Outcome might be limited to behavior or skill level. |

Learning questions could stimulate doubting. Although doubting is often perceived as being negative, I think it can be highly effective in combination with good decisionmaking. Finding and asking the right questions is often more difficult than answering the questions that are most available. In example 3 we are invited to consider if it would help to phase our negotiations and to think about possible ways to prepare (including tactics and behaviors). Outcome might be on a metacognitive or mindset level. |

| The fact that with learning objectives we state more clearly the desired outcomes, means that we are more likely to reach expected learning outcomes and that we will be better able to measure learning (on the learning level, not necessarily on the behavior, result or ROI level). | With learning questions, the learning outcomes might be harder to measure, mainly because they are to a large extent unpredictable. However, the value of the unexpected outcomes might be higher than any outcome we could have expected or measured, especially because they are the product of the learner’s individual learning process. I can imagine this depends greatly on the content domain of the learning. |

I know the comparison is not always accurate, but I hope to -at least- raise a few questions for those who are struggeling with explaining the purpose of learning initiatives (starting with myself).

Q: Do you have any experience with this? Are you curious about giving it a try?

Q: Would you like me to try to transform one of your learning objectives? If yes, please fill in the form below.

Your message has been sent

What do we do when we observe something that -in our experience- cannot be true? Do we really make it right in our minds, even if it means we’re kidding ourselves? I would really like to think that I’m not doing that, but probably there is no way of knowing that… right? If we want to consider all the options, even the seemingly impossible ones, we should stop kidding ourselves!

In a previous post “The future has a way of arriving unannounced“, I argue that in order to strive for a situation where we are aware of all the options we have, what I call the options optimum, we should not only search for options, but also allow ourselves to find options we were not looking for. Serendipity. Now, if we really want to be good at that, we should probably not only be good at finding stuff we recognise, but also stuff we think cannot be. Right?

So maybe we should distinguish two types of serendipity (yes, I like structure, can’t help it), defined as:

- Serendipity of the known: The talent to find stuff we were not looking for, but recognise as something we can use.

- Serendipity of the unknown: The talent to find stuff we were not looking for, did not recognise and didn’t even know were possible.

Striving to develop these talents can probably make us less biased, better at weak signal detection, and eventually even more creative. The better our receiving capabilities (See post “Optimising my receiving, processing and sending capability“), the better we can make sense of things.

A wonderful example of people unconsciously ignoring observations to make right what cannot be is the following video by Derren Brown.

Person swap, Derren Brown

Serious disclaimer: I’m not pretending to be genious, this whole blog is just one big experiment doomed to fail beautifully! 😉