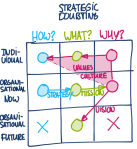

In the previous post (“How does my personal identity compare to my organisation’s identity?“) I described what elements I think communication about a company’s (or team’s) strategy should include (image below on the left). Now, let’s have a look at how that picture compares with how we normally commuicate about our strategy.

If we assume our strategic communication should make as many connections between the current and future what, how and why of the company and its employees as possible, it will be an interesting excercise to look at what ‘connections’ we usually focus on. In my post “What does strategic doubting look like“, I had a look at how I think mission, vision etc. compare to the what, how and why (see image below on the right). Now, let’s try to take that a step further.

What should a strategy look like What should a strategy look like |

When we communicate about values, or business principles, for me that -ideally- connects the company’s current why (why 3 in image below) and my current why (why 1). I say ‘ideally’, because I think it’s tricky to draft descriptions of values that are more than ‘buzzwords’. It would be interesting to see if we can strengthen this connection, e.g. by investigating what our common beliefs are. Knowing which beliefs I share with the company I work for will give me a feeling that I belong here. That doesn’t mean that we should agree on all beliefs and values, even a discrepancey can motivate me to start a debate about it with colleagues and potentially steer the company towards a differnt why. Ofcourse, the company (read: people in strategic positions) should allow for ‘movements’ like this to grow, otherwise a ‘difference in beliefs’ can lead to unrest.

Conecting the elements of what a strategy should look like for me

Conecting the elements of what a strategy should look like for me

Communicating about our company’s strategy, e.g. in quarterly strategic updates, we usually focus on the strategy in the strictest sense of the word, meaning the choices we made as an organisation, and the plans we made to make it happen. So during those publications or townhall meetings, we only make a connection between our organisation’s current how and what (how 3 and what 3). For the audience of these communications, it can be hard to ‘listen to the why’ of the strategy or to see the personal relevance of it. It requires quite a lot of effort to see how what I do individually contributes to the bigger picture (connecting what 1 and 3). It is hard to align because the organisation’s plans are too high level to link to my personal plans. Somehow, we have to find a way to specify overall choices to my particular situation. However, even if we manage to do that, still something is missing.

I’m not sure if in most companies it is common to communicate about the company’s mission, but -if it’s a good one- I think that could be very valuable. I say ‘if it’s a good one’ because there is a risk that companies, especially big ones, focus too much on the how and the what, and ‘reverse engineer’ their why for marketing purposes. Sometimes, the main focus is on measurements of success (e.g. cost-income ratio or profit) and the scope is quite short term (See comment from Eric Sforza on my post “What does strategic doubting look like“). The value of communicating a good mission statement is that it explains why we made the choices that we made as a company. It provides some meaning to what we do. Probably the same thing can be said about the company’s vision, that should probably precede the mission.

This together leads to what you could call the company’s strategic storyline, explaining:

- What we want the company to look like in the future (what 4), followed by

- Why we want it to look like that and what is guiding us on our path towards that future (why 3), followed by

- What choices we’ve made to make sure we reach that ideal future (what 3), and

- Provide focus to help people make choices on their individual contributions (what 1), followed by

- How we are going to act on these choices, what methods we will use (how 3), and

- What wkills and capabilities we need to act on these choices (how 1)

I think this storyline can be used for the overall strategy of the company, but also for different sub-strategies, e.g. on a specific product or service. It provides some context and relevance to what we are doing, which I think is neccessary for people to buy in to it. That said, I feel there are more ways to ‘connect our strategic dots’. For one, there still is a disconnect between most of the ‘future dots’ and ‘current dots’, and maybe we should include some historycal background as well (see next post).

Q: What do you think of the concept of a strategic storyline?

How do we select the right people to help us bring the organisation to where we want to be in the future? How can we get everybody aligned with our corporate or team-strategy? How can I communicate my strategic plans in a way that people will feel motivated to work with me on it? Do these questions sound familiar?

Have you ever thought that, even though you might be convinced your strategy is a good one, you have a hard time explaining it to others? Do you recognise it that people often use the same old ‘buzzwords’ to explain their strategy? And that these ‘soundbites’ are pretty much what for all companies strive for? I agree that a strategy, and communication around it should generic enough to make it possible for everybody in the organisation to feel part of it. But at the same time, it should specific enough to motivate individual employees to feel part of it.

So how can we craft a motivating strategy, and how can we communicate it? To start answering that question, first of all we have to ask ourselves: “what is strategy?“. In my post “What does strategic doubting look like?“, I described it as: “the plan, the organisation has to reach its vision, and the methods it is deploying to implement those plans”. I also gave my definition of mission (“the company’s purpose and plans/choices to pursue that purpose”), vision (“what the company will look like in the future if it continues to pursue its purpose”) and values (a set of why’s that all stakeholders of the organisation share and use when making choices).

In my opinion, when most people talk about strategy, they don’t talk about its relevance, but rather about how to implement it. Does ‘aligning’ and ‘cascading down’ sound familiar? In my opinion, both (and probably more) should be in the mix. In a couple of posts to come -starting with this one-, I will try to explain my take on this.

How for me a strategy should be described

For me to embrace my company’s strategy, I have to see the relevance of it for myself. I can only relate to it if I can see the value of it for me personally, now and in the future. The image above describes (part of) how I would like to see my company’s strategy presented. In one picture, I should be able to see how my ‘personal identity’ compares to ‘my organisation’s identity’. And I should be able to see if we have a future together.

Maybe not the most dificult part of the picture is to describe strategy as a shared direction (I share ‘my what’ with ‘my organisation’s what’, the green part of the arrow). If I can see what choices Our strategic futuremy organisation is making, I can see if there is a match with the choices I am making. And, better yet, I can choose to adapt my choices to those of my organisation. In order to do that, I have to be able to specify the overall strategy of my organisation to my specific situation. Which of my organisation’s choices affect me? To which choices can I contribute? No rocketscience so far, right?

Slightly less obvious however, is to describe strategy as a set of core capabilities (My ‘organisation’s how’ and how ‘my how’ can contribute to that, the blue part of the arrow). If I would know what my organisation considers it’s core capabilities, what my organisation is really good at, I probably would feel a little proud to be part of that. If I would know how my team’s capabilities, together with othet teams’ capabilies add up to a picture of what we are good at as an organisation, I think it would motivate me. If I’m motivated by what I’m good at (See ‘mastery’ in post “Why do I do it? – Motivation“), I think I would be motivated by knowing what we are good at collectively. Maybe a stretch, but still interesting I think.

Most powerful for me personally is to describe strategy as a set of shared beliefs (‘My why’ is ‘my organisation’s why’). Knowing what my organisation beliefs in gives me the opportunity to consider if I belief the same. Knowing what my organisation considers its ‘dot on the horizon’, and what beliefs and values are guiding it in its choices, help me evaluate the relevance my own choices and actions. Why am I doing what I do?

Q: Do you agree with my reasoning? Do you agree that communication around strategy is often focused on strategy as a shared direction?

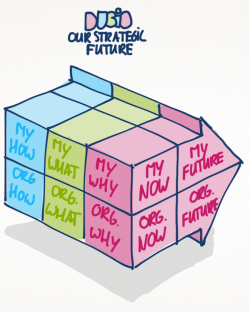

In an experiment to 1) see how I can visualise three variables in a cube-style image, and 2) to see what happens if I multiply the what-, how- and why questions with two perspectives at the same time (in this case an organisational- and time-perspective), I drew the image below. Besides it being a visualisation excercise, I wanted to see if the ‘crossing’ of three interesting variables would lead to a new, even more interesting insight. I believe crossing or multiplying variables is interesting to do, but I also believe it’s only a sense-making method, that requires some context and follow up to have any actual value.

To explain what I mean with this “27-cubed-cube”, let me briefly discuss four of the small cubes:

- The top left cube represents my current how. That could be the skills, methods and tools I currently have access to.

- Cube number two would be called our short-term what, meaning short term plans, choices that we’ve made for the short-term, or options that we could potentially choose in the near future.

- The third is my long-term purpose, like my values or motives (that are not likely to change), and my long-term ‘needs and wants’.

- And the cube at the bottom right corner symbolises the the current purpose of the organisation I work in. I think corporate values and business principles could fit to this cube.

Maybe… just maybe… the process of describing all twenty seven cubes for my particular context could help me become more aware of my professional identity. It could be a good starting point to not only understand my ‘playing field’, but also provide pointers to change something. After all, most agree that the key to better performance or more work satisfaction is often found in the environment (team or organisaitonal), rather than the individual.

Q: Does this resonate with you? Should I add the past to the cube’s time-axis?

In a number of posts, I’ve refered to Daniel Pink, and his view on motivation (e.g. post “Why do I do it? – Motivation“). I feel it has a strong link with the what-, how- why-questions (See page “Dubito ergo sum“), and I tried to visualise that in the following picture.

If the choices we make are called ‘the what’, autonomy could be called your ‘what-freedom’? It is motivating to choose your own what. If we would describe the things we do as ‘the how’, then mastery would be ‘being good at the how’. The things we find important, ‘the why’, determine our purpose, or ‘why we do things’, right?

Q: Dear reader, does this comparison fly for you?

If I combine my last three posts “In the middle of difficulty lies opportunity“, “From sense-making to scenarios“, and “The future has a way of arriving unannounced” in one picture, I think it would look something like this bow-tie shape:

I think the previous posts explain my line of thinking, I’ve just added them up into one graph. I’ve added a big WHAT on top, as I think all the elements described in my picture, wheather it’s sense-making or decision-making, are about the what. What options do I have? What choices do I make? True, you can use your skills and certain methods to make this process happen (how), but most of the value lies in the results (what).

Q: Do you think these steps (find info, make sense, etc.) represent skills everybody should master?

Image on top of page: Rock formation in Torres del Paine, Chile (own photo)

What do I base my decisions on? Admittedly, it’s usually on present circumstances (See post “”When am I?“). But suppose I have to make a decision that is a little bit more complicated and long term, how could I best go about that? How do I make decisions for my future self, instead of only for my current self (See post “Choosing is a choice“)? How can I increase my ability to shape my own ideal future?

In my post of some days ago, “In the middle of difficulty lies opportunity“, I described the diverging process of creating options and the converging process of choosing from those options. Not totally satisfied with the answers the model provided my, I’ve now added two extra variables to the mix: value and predictability.

Let me explain the picture:. To be able to make the most valuable (y-axis) options, you need some time (A to B) to look for what all the options are. However, by searching, you will only see the options that you expect, or can predict. The trick is to also find options that you did not expect, and could not predict.

In my opinion, for abovementioned reason, searching for options is not enough. To optimise the amount of options we can choose from in moment B, we need to learn ourselves the talent to find stuff that we were not looking for, but can very well use. I guess you could call that serendipity. Question is, how do I increase my serendipity? Probably the answer lies in a combination of increasing my ‘receiving ability’, fighting my biases and navigating myself in situations where ‘beautiful accidents’ might happen. I feel very strongly that this is one of the keys to a better ‘diversity of thinking’ and ‘autonomy of choosing’.

At timepoint B, when we have exhausted our searching and serendipitous capacity (or just decided it’s time for some breakthrough), we are at what I call the options optimum or moment of optimal autonomy. At this point we should have a range of options or scenario’s to choose from. Obviously, the trick is to choose the most valuable one (to us or to those important to us). Since we’ve combined searching and serendipity, there should be a wider range (I to II for searching and II to III for serendipity) to choose from. A bit simplistically, for this picture, I’ve assumed that more options also means more value, because there is a chance that serendipity has lead to a more valuable option than searching along. Still with me?… sure hope so… Regardless of that, still there should be added value to serendipity. After all, according to Daniel Pink (See post “Why do I do it? – Motivation“) autonomy is motivating. So that would be now-value, and not future-value…. again, hope you are still with me…

Having a lot of options might be a comfortable state to be in, but is not enough to satisfy my future self, I have to follow them op with some choices. The fact that I commited to serendipity in the time from A to B, I can now imagine a future that I could not have predicted at point A, my unpredictable future is now within reach. Maybe the main lesson in this is that I should always be aware that there are a bunch of unpredictable futures out there. I think that’s a very cool insight… keeps me curious. So having an idea of your predictible (potential) futures, and at least some of your unpredictible (potential) futures is probably a good starting point for making valuable choices.

Q: For whoever is still with me… does this make sense to you? Do you think it’s too obvious to deserve a post of this length (haha, probably)?

Image on top of post: “Reach for the future” on the blog “Imaginarium of the revolving future“. Title: quote by George Will, journalist

Following up on my previous post (See “In the middle of difficulty lies opportunity”), I’ve zoomed in on the first part of the decision making process I described, how to generate options. Building on the assumption that having many options is a good thing, I logically asked myself is: “How do I generate options?”.

Again, I will try to describe my thinking process:

- From some sets of options, it’s more difficult to choose than from other sets

- What are the best kind of options in terms of ‘ease of choosing’?

- Can you say that ideas lead to options, lead to scenario’s? If yes, are scenario’s the easiest to choose from?

- To generate ideas and ‘mature’ them into options or scenario’s you need knowledge.

- So before you can start generating scenario’s, you need a sense-making process

The sense-making process is what I tried to visualise in the left-side of the drawing below, where I go from information, via concepts, to meaning. Before synthesizing knowledge into ideas, I have to analyse the information available to me.

The way I see it (at the moment), this drawing could be glued on the front end (left side) of the previous drawing, where the’diverging’ part of this drawing would overlap the ‘diverging’ part of the previous drawing.. Although, this drawing ends with scenario’s and the previous with options, I still think it’s an interesting proposition.

Do you recognise that during meetings some people keep on talking about ideas, while others just want to hear about practical stuff? And how difficult it is to get anything done if that’s the case? Intrigued by the complexity of choosing, decision making and opportunity, I have been trying for a while to make some sense of it all. What is the difference between options and choosing, how do concepts like creativity, focus and decision making fit in? Triggered by a quote from Einstein (thanks to a tweet from David Gurteen), I decided to write a post about this (probably missing Einsteins point but ok).

The problem is that both finding out what your options are, and choosing from the options that you have found is a difficult thing to do, and yet crucial for doing (and feeling) well. Limited by perception, (un)focused attention and bias, we are not very good at ‘seeing’ all the options that are available to us. And then, even more difficult, we are paralysed by our anxieties to choose (See post: “The pacifying ideology of choice”), again bias, and lack of ‘internal compass’ when we have to choose from the options we have.

Please follow my thinking and have a look at the scribble below:

- To be able to choose, you have to have options

- The more options you have,

- … the more valuable choices you can potentially make

- … the more difficult it is to choose

- … the more autonomy and control you experience (which is good, see post “Why we do it? – Motivation”)

- In order to know which choices would be most valuable, you have to know what you want.

- So more options = better and nicer, but more difficult

- Creativity and innovation are good, because they lead to more options.

Explanation:

Creating options On the left side of the picture, as we move to the future, we start with generating options, trough e.g. creativity. The less biased we are, the more options we will see. Some love doing this, and others hate it as it costs time and the practical value can be hard to see (the graph will be wider). I guess doubting, and generating questions, will help create more options (See post “The dubio-engine – Accellerate your (self-) awareness“).

Options-optimum Then comes the moment where we have enough options (in the middle), depending on how successful we were in the first phase. This point can be experienced as ‘being in control’, or being autonomous, which can be motivating.

Decision making And then, we can start focusing on our final choice. Ideally we weigh all the options and evaluate them on the value for us (and hopefully others involved).

Both phases can be focused on the what, the how or the why. The creating options process can be about purpose (e.g. why would somebody do x?), or the what (e.g. what else can we do). And the decision making phase can be about deciding what to do (what), or about putting the decisions in to practice (how).

Q: Does this make sense to you too? Do you recognise how some people keep talking ‘diverging’, and others ‘converging’ during meetings?

Image on top of post, source Flickr

“I choose not to choose life. I chose something else. And the reasons? There are no reasons. Who need reasons when you’ve got heroin?” (From the movie Trainspotting, see below)

I’m so lucky. I have everything I need, I’m healthy, and I have seemingly unlimited opportunities to do what I want. It’s the easiest starting point for any action I can think of, but yet it’s the hadest thing to get started. Regardless of all possible anxieties (what will others choose, choosing is loosing, what is the ideal choice, see post “The pacifying ideology of choice“) I have to choose to make some choices or I will end up in a passive state of indicisiveness. And the trick is, I find it easier to make choices that are nice to make, and less limiting (e.g. buying a hamburger) than choices that are quite limiting and only nice in the long run (e.g. going on a diet).

So I have to remember to make choices for my ‘current self’ and my ‘future self’ (See post “When am I?“)… sigh…

Introduction to the movie Trainspotting (1996)